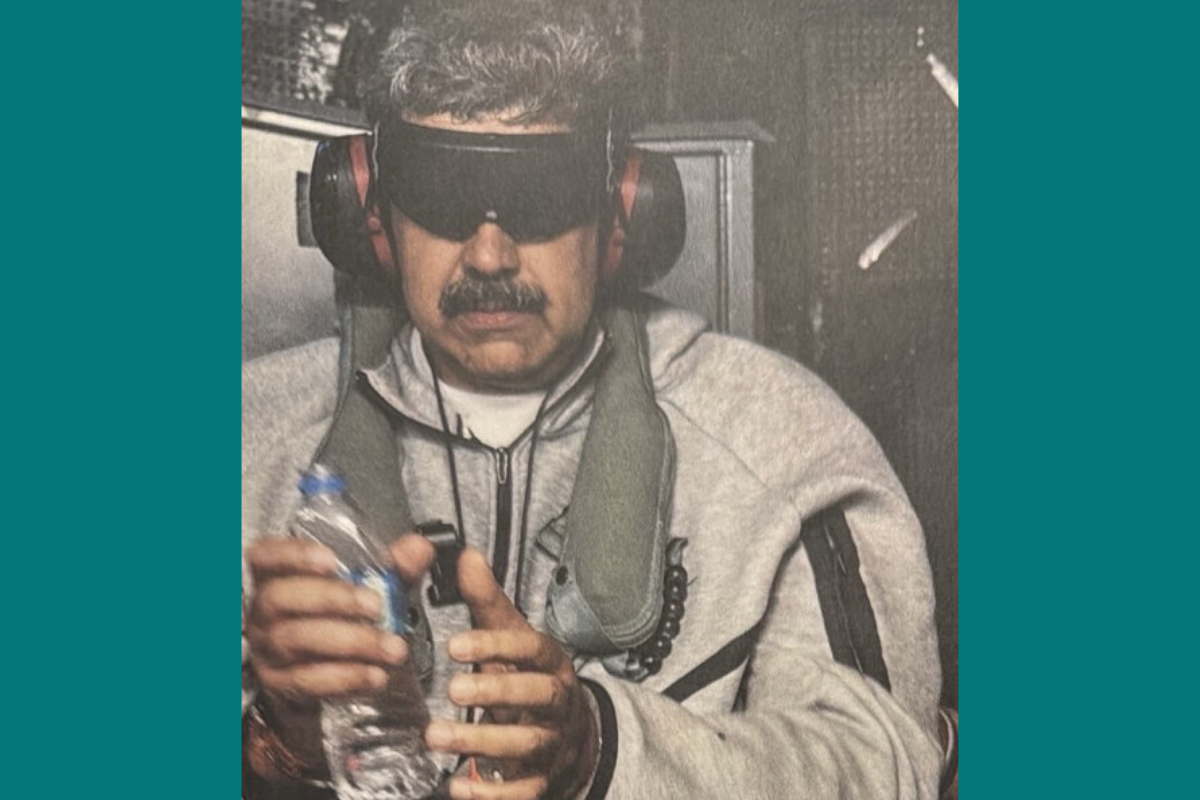

President Donald Trump delivers remarks at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, following the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, Saturday, January 3, 2026. (Official White House Photo by Molly Riley/Public Domain)

Opinion by Monica Duffy Toft

An image circulated over media the weekend of January 3 and 4 was meant to convey dominance: Venezuela’s president, Nicolás Maduro, blindfolded and handcuffed aboard a U.S. naval vessel. Shortly after the operation that seized Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, President Donald Trump announced that the United States would now “run” Venezuela until a “safe, proper and judicious transition” could be arranged.

The Trump administration’s move is not an aberration; it reflects a broader trend in U.S. foreign policy I described here some six years ago as “America the Bully.”

Washington increasingly relies on coercion — military, economic, and political — not only to deter adversaries but to compel compliance from weaker nations. This may deliver short-term obedience, but it is counterproductive as a strategy for building durable power, which depends on legitimacy and capacity. When coercion is applied to governance, it can harden resistance, narrow diplomatic options, and transform local political failures into contests of national pride.

There is no dispute that Maduro’s dictatorship led to Venezuela’s catastrophic collapse. Under his rule, Venezuela’s economy imploded, democratic institutions were hollowed out, criminal networks fused with the state, and millions fled the country — many for the United States.

But removing a leader — even a brutal and incompetent one — is not the same as advancing a legitimate political order.

Force Doesn’t Equal Legitimacy

By declaring its intent to govern Venezuela, the United States is creating a governance trap of its own making — one in which external force is mistakenly treated as a substitute for domestic legitimacy.

I write as a scholar of international security, civil wars, and U.S. foreign policy, and as author of “Dying by the Sword,” which examines why states repeatedly reach for military solutions, and why such interventions rarely produce durable peace. The core finding of that research is straightforward: Force can topple rulers, but it cannot generate political authority. When violence and what I have described elsewhere as “kinetic diplomacy” become a substitute for full spectrum action — which includes diplomacy, economics, and what the late political scientist Joseph Nye called “soft power” — it tends to deepen instability rather than resolve it.

More Force, Less Statecraft

The Venezuela episode reflects this broader shift in how the United States uses its power. My co-author Sidita Kushi and I document this by analyzing detailed data from the new Military Intervention Project. We show that since the end of the Cold War, the United States has sharply increased the frequency of military interventions while systematically underinvesting in diplomacy and other tools of statecraft.

One striking feature of the trends we uncover is that if Americans tended to justify excessive military intervention during the Cold War between 1945-1989 due to the perception that the Soviet Union was an existential threat, what we would expect is far fewer military interventions following the Soviet Union’s 1991 collapse. That has not happened.

Even more striking, the mission profile has changed. Interventions that once aimed at short-term stabilization now routinely expand into prolonged governance and security management, as they did in both Iraq after 2003 and Afghanistan after 2001. This pattern is reinforced by institutional imbalance. In 2026, for every single dollar the United States invests in the diplomatic “scalpel” of the State Department to prevent conflict, it allocates $28 to the military “hammer” of the Department of Defense, effectively ensuring that force becomes a first rather than last resort.

“Kinetic diplomacy” — in the Venezuela case, regime change by force — becomes the default not because it is more effective, but because it is the only tool of statecraft immediately available. On January 4, Trump told The Atlantic magazine that if Delcy Rodríguez, the acting leader of Venezuela, “doesn’t do what’s right, she is going to pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro.”

Lessons From Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya

The consequences of this imbalance are visible across the past quarter-century.

In Afghanistan, the U.S.-led attempt to engineer authority built on external force alone proved brittle by its very nature. The U.S. had invaded Afghanistan in 2001 to topple the Taliban regime, deemed responsible for the 9/11 terrorist attacks. But the subsequent two decades of foreign-backed state-building collapsed almost instantly once U.S. forces withdrew in 2021. No amount of reconstruction spending could compensate for the absence of a political order rooted in domestic consent.

Following the invasion by the U.S. and the surrender of Iraq’s armed forces in 2003, both the U.S. Department of State and the Department of Defense proposed plans for Iraq’s transition to a stable democratic nation. President George W. Bush gave the nod to the Defense Department’s plan.

That plan, unlike the State Department’s, ignored key cultural, social, and historical conditions. Instead, it proposed an approach that assumed a credible threat to use coercion, supplemented by private contractors, would prove sufficient to lead to a rapid and effective transition to a democratic Iraq. The United States became responsible not only for security, but also for electricity, water, jobs, and political reconciliation — tasks no foreign power can perform without becoming, as the United States did, an object of resistance.

Libya demonstrated a different failure mode. There, intervention by a U.S.-backed NATO force in 2011 and the removal of dictator Moammar Gadhafi and his regime were not followed by governance at all. The result was civil war, fragmentation, militia rule, and a prolonged struggle over sovereignty and economic development that continues today.

The common thread across all three cases is hubris: the belief that American management — either limited or oppressive — could replace political legitimacy. Venezuela’s infrastructure is already in ruins. If the United States assumes responsibility for governance, it will be blamed for every blackout, every food shortage, and every bureaucratic failure. The liberator will quickly become the occupier.

Costs of ‘Running’ a Country

Taking on governance in Venezuela would also carry broader strategic costs, even if those costs are not the primary reason the strategy would fail. A military attack followed by foreign administration is a combination that undermines the principles of sovereignty and nonintervention that underpin the international order the United States claims to support. It complicates alliance diplomacy by forcing partners to reconcile U.S. actions with the very rules they are trying to defend elsewhere.

The United States has historically been strongest when it anchored an open sphere built on collaboration with allies, shared rules, and voluntary alignment. Launching a military operation and then assuming responsibility for governance shifts Washington toward a closed, coercive model of power — one that relies on force to establish authority and is prohibitively costly to sustain over time.

These signals are read not only in Berlin, London, and Paris. They are watched closely in Taipei, Tokyo, and Seoul — and just as carefully in Beijing and Moscow.

When the United States attacks a sovereign state and then claims the right to administer it, it weakens its ability to contest rival arguments that force alone, rather than legitimacy, determines political authority. Beijing needs only to point to U.S. behavior to argue that great powers rule as they please where they can — an argument that can justify the takeover of Taiwan. Moscow, likewise, can cite such a precedent to justify the use of force in its near abroad and not just in Ukraine.

This matters in practice, not theory. The more the United States normalizes unilateral governance, the easier it becomes for rivals to dismiss American appeals to sovereignty as selective and self-serving, and the more difficult it becomes for allies to justify their ties to the U.S. That erosion of credibility does not produce a dramatic rupture, but it steadily narrows the space for cooperation over time and the advancement of U.S. interests and capabilities.

Force is fast. Legitimacy is slow. But legitimacy is the only currency that buys durable peace and stability — both of which remain enduring U.S. interests.

If Washington governs by force in Venezuela, it will repeat the failures of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya: Power can topple regimes, but it cannot create political authority. Outside rule invites resistance, not stability.

Monica Duffy Toft is the Director of the Center for Strategic Studies at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a professor of International Politics.

Donate and Keep Us Paywall-Free

Help us reach our $50,000 goal to power next year’s reporting, community storytelling, and a new audio documentary on Puerto Rico.

And now a word from our sponsor

Get the 90-day roadmap to a $10k/month newsletter

Creators and founders like you are being told to “build a personal brand” to generate revenue but…

1/ You can be shadowbanned overnight

2/ Only 10% of your followers see your posts

Meanwhile, you can write 1 email that books dozens of sales calls and sells high-ticket ($1,000+ digital products).

After working with 50+ entrepreneurs doing $1M/yr+ with newsletters, we made a 5-day email course on building a profitable newsletter that sells ads, products, and services.

Normally $97, it’s 100% free for 24H.

What We’re Reading

Venezuela and Messaging Apps: Over at Pressing Issues, the newsletter I edit for my day job at Free Press, I connected with Roberta Braga of the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) about the messaging app analysis they released hours after Maduro’s capture.

Americans and Venezuelans: From the Associated Press, “polling conducted in the immediate aftermath of the military operation that captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro suggested that many Americans are unconvinced that the U.S. should step in to take control of the country.”

Julio Ricardo Varela edited and published this edition of The Latino Newsletter.

The Latino Newsletter welcomes opinion pieces in English and/or Spanish from community voices. The views expressed by outside opinion contributors do not necessarily reflect the editorial views of this outlet or its employees.