I am a public health professor and have studied deportation for a decade and a half, paying particular attention to the laws, policies, and off-the-books strategies that make deportation so harmful to individuals, families, and communities. I have written about deportation during the Obama, Biden, and both Trump eras.

While some enforcement strategies have remained the same across administrations, the Trump administration has leaned into something I had not seen before: the administration wants the “chilling effect” of deportation to affect everyone who supports immigrants, not just immigrants themselves. That is, if you support immigrants, it could cost you your job, your health, or even your life.

Empirical evidence shows that fear of deportation confirms this “chilling effect” — or an avoidance of public services, healthcare, and everyday activities due to fear of deportation — on undocumented immigrants and harms their health.

For example, research shows that expectant mothers will avoid prenatal care if they fear they are at risk of deportation, whether because they do not trust the clinic with their medical records or they fear they will be racially profiled and arrested while driving to get services.

The chilling effect does not stop at undocumented immigrants.

Undocumented parents often avoid applying for supplemental food assistance for their U.S. citizen children, even though those children are eligible. These effects are also community-wide, as Latino mixed-status communities avoid medical services and decrease their trust in the police, wary that a call — such as a domestic dispute — could result in the deportation of someone who happens to be present.

But it is generally accepted that white U.S. citizens who can neither be racially profiled nor deported — or have a family member deported — are untouched by the chilling effects of Trump’s deportation agenda. But the Trump administration is making a concerted effort to change this by increasing the violence and chaos of immigration enforcement, detaining immigrants far from their homes, and, as we see now, physically harming those who support immigrants, regardless of race or citizenship.

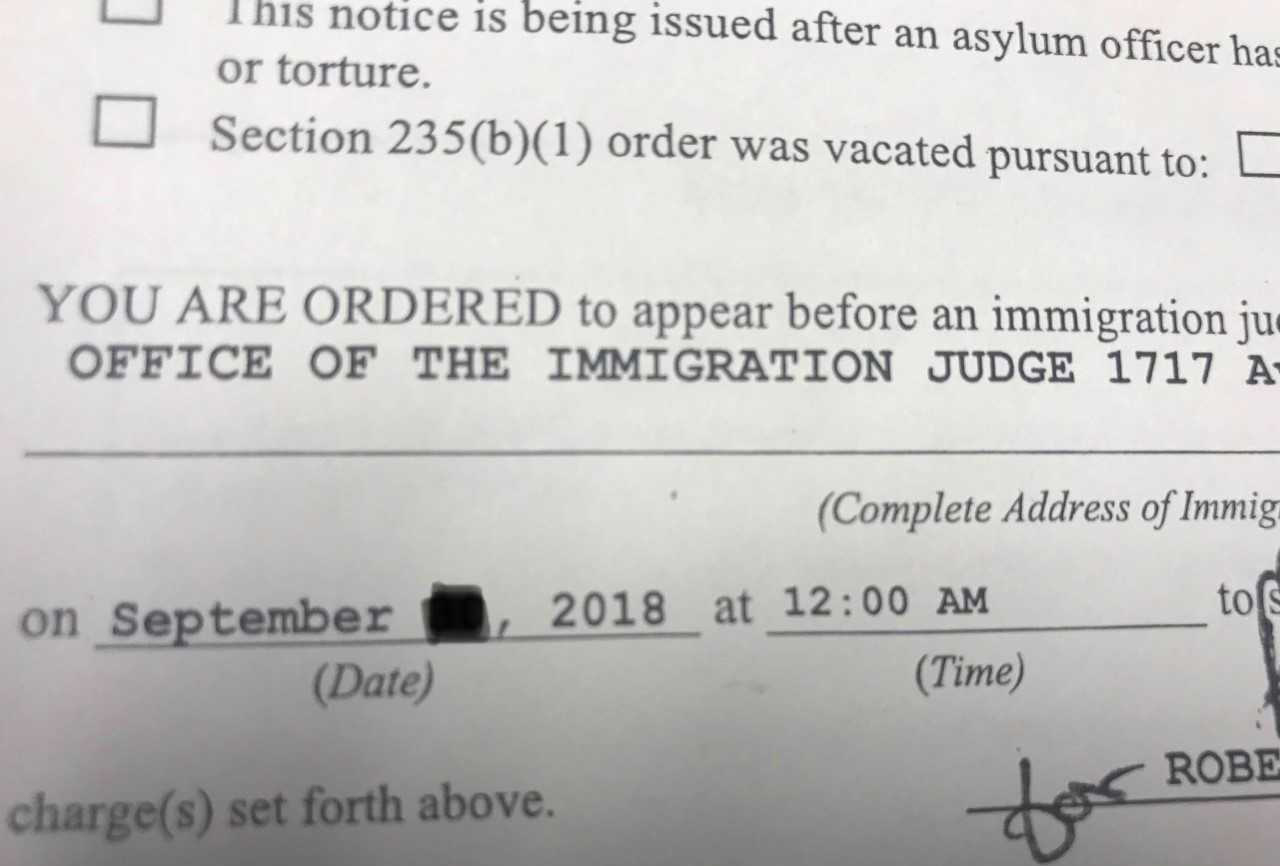

We spoke with a law student who responded to the raids in O’Neill, Nebraska, in 2018. She told us that after hearing about the raids, she drove two hours and 45 minutes to O’Neill to support the families of those detained, working around the clock for days. When she finally had a moment of downtime, she reflected, “I took a bathroom break at one point, and I didn’t realize how intensely emotional it was until I had to throw up in the bathroom because I was so anxious and stressed from hearing all the things that the people were telling me.”

Her story of throwing up in the bathroom because of the trauma of working with a community in which 133 workers had been detained in one day is only one such story of many. While proud of the work they did to support immigrants, many found themselves at psychological and emotional breaking points because of what they experienced while doing so. And, as with this law student, much of the exhaustion came from the hours-long drives required to provide the support.

An organizer who had taken master’s level courses in social work probably put it best when I spoke to her in the office of her organization in Norwalk, Ohio, after she responded to the raids in both Sandusky (half an hour away) and Salem (two hours away): “It’s infuriating. It’s devastating. We were working around the clock until midnight every day for months. And it was completely exhausting. To me, it felt like vicarious trauma.”

Research shows that vicarious trauma can lead to trauma symptoms that mimic those of the people who experienced the trauma themselves. This means that the sweaty palms, the shortness of breath, the intrusive thoughts, or the vomiting experienced by those about to be deported can also be felt by those who supported them.

The Trump administration has explicitly leveraged the “chilling effect” of deportation, hoping to make life so miserable for undocumented immigrants that they self-deport and take their families with them. The killings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti show that your citizenship, skin color, a Permit to Carry, and First Amendment rights will not protect you from the deportation machine. Even if you can’t be deported, your support of immigrants will cost you dearly.

For those of us who support immigrant communities, we must take into account that breaking us down and chilling us into silence is part of the strategy, and integrate this into our organizing. How to do so? We can turn to both public health research and to the people of Minnesota and remember the necessity of mutual aid and community care. Now more than ever, care for others requires care for each other.

Dr. William D. Lopez is a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health and Faculty Associate in the Latina/o Studies Program. He is the author of Raiding the Heartland: An American Story of Deportation and Resistance, a follow-up to his award-winning first book, Separated: Family and Community in the Aftermath of an Immigration Raid. Dr. Lopez regularly contributes to public discussions on deportation, diversity, and Latino culture in outlets such as the Washington Post, CNN, San Antonio Express-News, Detroit Free Press, and Truthout. He is on the boards of Health in Partnership and The Latino Newsletter.

The Latino Newsletter is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Help us reach our $50,000 goal to fund our podcast’s third season and to offer more opportunities for journalists to file their stories without paywalls or paid subscriptions.

What We’re Reading

The Latino Media Consortium’s Statement on Journalists’ Arrests: From the Latino Media Consortium’s LinkedIn page, “The Latino Media Consortium condemns the arrest of journalists Don Lemon and Georgia Fort, the most recent targets in an alarming and accelerating assault on press freedom in the United States. Their arrests and detention for covering an anti-ICE protest mark a dangerous escalation in the criminalization of journalism.”

The Latino Newsletter is a founding member outlet of the Latino Media Consortium.

Julio Ricardo Varela edited and published this edition of The Latino Newsletter.

The Latino Newsletter welcomes opinion pieces in English and/or Spanish from community voices. Submission guidelines are here. The views expressed by outside opinion contributors do not necessarily reflect the editorial views of this outlet or its employees.