In May 1898, my great-grandfather José Santiago Pagán was fifty-eight; thirty-three years of his life enslaved. His wife, Josefa, was a year younger, also born in slavery. They now labored in the same hacienda where they’d always lived. The hacendado, don Nicanor, preferred to oversee the harvest managed by mayordomos. His three sons worked alongside him and lived in the hacienda most of the year, taking turns visiting their homes in the capital where their wives’s charity and church activities upheld the family's status in San Juan society.

In early May, Nicanor charged José to deliver fruits, vegetables, smoked meats and other farm-made supplies to his wife and daughters-in-law. José had been on this road many times on the same kind of errand, but now as his cart approached the city, he was surprised by the crowds heading in the opposite direction.

A horseman ahead of a cart loaded with crates, rocking chairs and other furniture precariously roped together called out to José.

“Go back!” Behind the cart, a passenger coach was filled with women and children. “They blocked the harbor and will bomb the city!”

He rode off without saying who “they” were. If José returned to the hacienda with news that the city was being bombed, don Nicanor would ask why he’d abandoned his family in danger. On the other hand, maybe doña Sifronia, the three daughters-in-law, their children and servants might be among the muchedumbre leaving the Capital and might reach the hacienda before José could look for them in the city. He’d known doña Sifronia all his life and thought it was best to ride against the current of those fleeing toward the highlands.

Doña Sifronia had lived in San Juan through innumerable civil disturbances leading up to abolition, mutinies by soldiers posted in El Morro, insurrections, a cholera epidemic, disastrous hurricanes and an earthquake. If anyone could face another challenge, it would be doña Sifronia. As José continued on his errand, he watched for the family’s wine-colored coach and the familiar two sturdy horses that had made the trip from the city to the hacienda and back so many times, they could do it without human interference.

When he reached Puerta de Tierra, José invoked don Nicanor and doña Sifronia until the sentries let him enter the city walls. Soldiers, horses, and military vehicles clattered upon the cobblestones adding to the chaos in the citadel under siege. He was stopped several times, but finally reached the alley to the back door of the family home.

“Gracias a Dios you've arrived, José. You can see what a mess we're in,” Doña Sifronia said. “Rogelito has catarrh and a high fever and Mili twisted her ankle. She can't walk more than a few paces and she too has been sneezing and coughing since yesterday morning.”

Doña Sifronia had been in charge of her city home, those of her three sons, her grandchildren and servants and was the intimidating matriarch of her daughters-in-law. None dared overrule her decisions.

“I never imagined Spain would declare war on the United States. ¡Es inconcebible! I understand the Yanquis have long coveted Cuba, but what do they want with us, a poor island so far from their shores? No, José, it's beyond comprehension. I didn't want to trouble Nicanor and only this morning sent a messenger with the news. You probably crossed paths. Over the last few days, Yanqui warships have been cruising close enough for us to see their sunburnt faces. Obviously, el Presidente McKinley plans to bomb us all to smithereens. ¡Es increíble! We’re a peaceful people with no quarrel with the United States. Their precious Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, not in ours. We had nothing to do with it! How can McKinley justify an attack on us? They’re barbarians! To be run out of my own home by Yanquis? ¡No! ¡Es insoportable, José! ¡In-so-por-table!”

José let her catch her breath.

“Disculpe, señora, but you and the family will be safer in your hacienda if they bomb the capital,” José pushed the air toward the tumult beyond her doors. “I have the cart, you have the family coach. If there’s to be cannon fire, we can go before it starts. It might be impossible to leave after.”

Doña Sifronia considered José's logic and it didn't take her long to accept the inevitable. She mustered the relieved daughters-in-law to select only what they could carry to the plantation. The house servants would remain behind to watch over the rest of their belongings.

As they packed, two bedraggled soldiers appeared at the back door to inform doña Sifronia that the cart, the bullocks pulling it, her carriage and horses had been requisitioned by the military command. Doña Sifronia knew the bullocks would end up in the slaughterhouse. The better cuts served to the officers while the rest, including the entrails, would be stews for the lower ranks. The horses might suffer the same fate.

“No son,” she said in her imperial tone. She spoke Castilian, not Puerto Rican, softening her final s into a whispered sh, enunciating c and z with a lisp, and gently scraping g and j across the back of her throat. "I know neither the governor or you would deprive me, my frightened daughters-in-law, one pregnant, and two feverish children the opportunity to find safety while you, our brave soldiers, beat the Yanquis back to their own shores, as you will most certainly do."

The two soldiers were awed. They were adolescents, and the one with most of his teeth had spoken for the other. Doña Sifronia had decided he’d been a petty criminal given the choice of spending time in a damp prison in Asturias (she recognized his accent) or be exiled for the duration of his sentence as a soldier in His Majesty’s service on an island in the Caribbean. He’d probably never stepped inside a home like hers, opulent by any standard, with gracious arches around the courtyard, an enclosed garden with a fountain gurgling in the center, and the elaborate mosaic tiles in the open galleries. The boys didn’t even know where to look before such splendor.

“I have orders, señora,” the boy gulped.

Doña Sifronia wasn’t about to let a mocoso from the hinterlands of Northern Spain tell her what to do. She also knew she couldn’t send him away empty handed. She had connections with the military governance and understood they didn't send a medaled soldier because they didn't expect her to follow orders. Still, a gesture was necessary.

“Your superiors, including our esteemed governor, have dined at our table,” she said. “I’m certain they will accept other donations in solidarity with the Spanish Crown and you, our courageous soldiers.”

Doña Sifronia had the maid offer them agua fresca while she dug out her plainest silver candelabra, her least expensive rug and a poorly painted retablo of the Holy Family, part of her youngest daughter-in-law's dowry. “You're welcome to the produce our José has just delivered.”

Before dawn the next morning, José guided the bullocks with doña Sifronia's most precious furnishings, trunks and chests on the cart. Crammed inside the coach, were the matriarch, her three daughters-in-law, and five children. Boxes and pillowcases filled with personal items they didn’t want to put in the open cart were stuffed where they could fit on the floor and as cushions for the babies. As they crossed the bridge connecting San Juan with the rest of the island, the first of the blasts from Yankee gun ships thundered behind them.

“Los Yanquis were supposed to warn civilians when they were about to bombard us,” doña Sifronia informed the daughters-in-law. “Abusadores! Even war has rules.”

They were met halfway to the plantation by Nicanor and Higinio, José’s youngest son. The news of the US Navy threatening San Juan had reached them and they’d set off on horseback to evacuate the women and children. Nicanor was grateful José had convinced doña Sifronia to leave.

“I was afraid she wouldn't leave,” Nicanor said. “Against all evidence, she still believes in the might of the Spanish Empire.” He took his eldest grandson, and Higinio the next oldest boy on their mounts to give the women more room inside the carriage.

They reached the hacienda that evening, and once he’d settled his family, Nicanor sent messengers to the barrios on the periphery of the plantation asking every male agregado twelve years old and older to report to his yard at sunrise the next morning. He had no weapons for them but suggested they sharpen their machetes and to use agricultural implements as necessary to defend themselves and their property against the United States.

He and other landowners organized brigades with their neighbors. Depending on political leanings, some prepared to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with the ill-equipped Spanish soldiers and local militias, others saw the conflict as an opportunity for Puerto Ricans to gain independence from Spain, and a minority welcomed the idea of a Puerto Rico Americano. Nicanor, a criollo born in Puerto Rico, aligned with those prepared to die for independence.

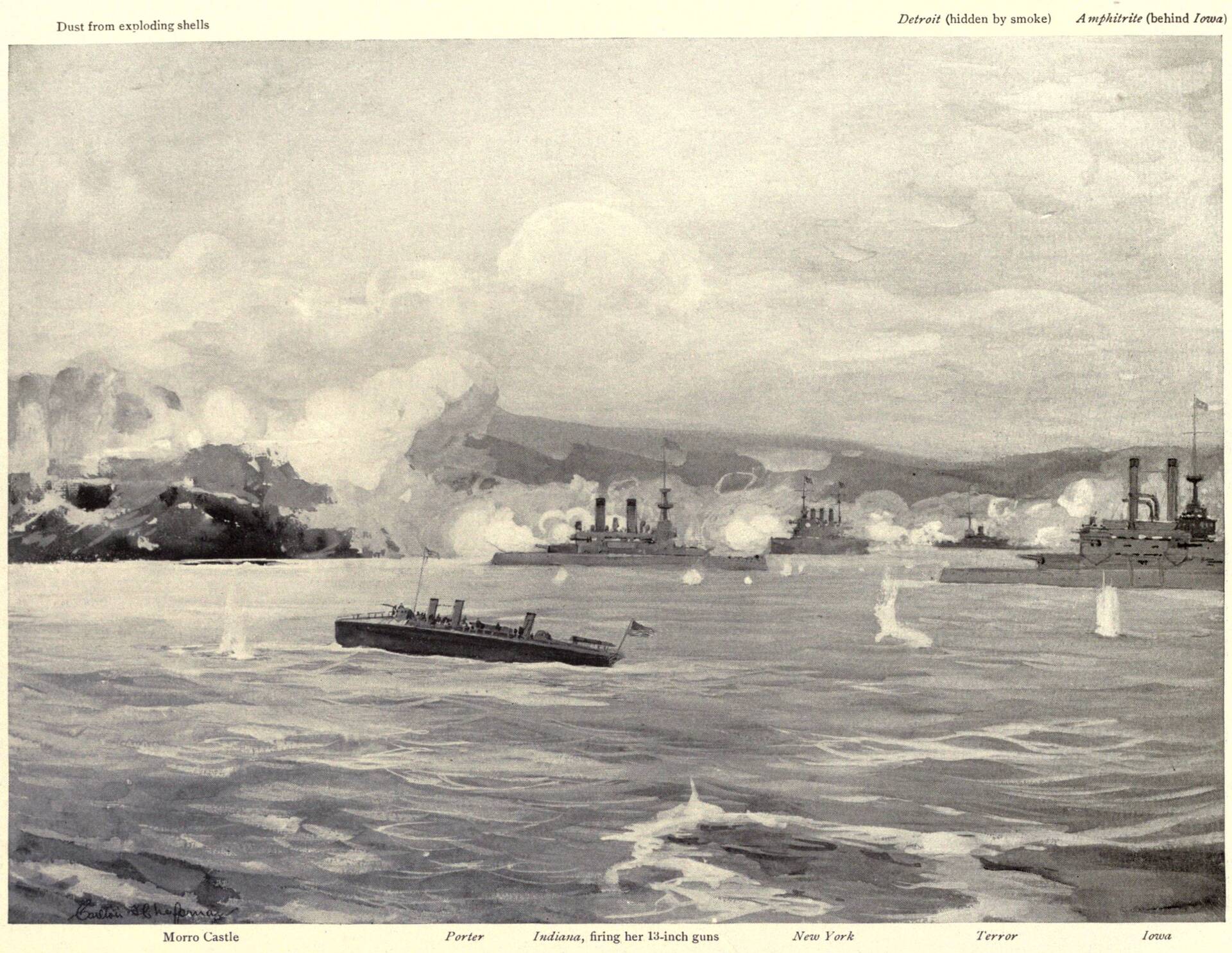

The famously impregnable El Morro protecting the Capital held fast during the bombardments in May, but the United States Navy blocked San Juan harbor to keep Spanish vessels at anchor from leaving or for arriving ships to supply munitions and personnel. In July, the Spanish fleet tried to break through the blockade and was swiftly destroyed by a US Navy squadron, killing 350 sailors and injuring 160 even as diplomatic discussions continued between the United States and Spain mediated by the French. Puerto Rican newspapers reported on the efforts to end the hostilities, but only the most literate in the larger cities could make sense of the reports, filtered through politicized lenses and censorship laws.

Through it all, campesinos and jíbaros worked the land, responded when called by those in power, or found ways to resist being recruited as soldiers with no weapons. Most had no particular commitment to any of the options the ruling-class propounded and encouraged. Eighty-five-percent of them were illiterate, scattered in subsistence farms or tumbledown barrios. They depended on rumor, tall-tales, and gossip that did little but keep everyone anxious about a future they could not imagine. Unaware, they were pawns between two nations whose leaders did not know or see them, but considered the land they tilled a prize in their war.

~•~

People like my great-grandfather José had no idea the United States had been edging toward war with Spain long before 1898. He’d never heard of the Monroe Doctrine and knew nothing about the sinking of the battleship Maine on February 15 in Havana Harbor that accelerated hostilities. In the United States, the two-hundred-sixty-one fatalities inflamed the tabloids. Their hysterical reports inspired young men to enlist to fight against the Spanish. Among them was twenty-year old Carl Sandburg, future poet, journalist, and champion of the working class.

In the early morning hours of July 25, Carl was sleeping fitfully in his bunk on a United States Army transport. Like most of the other newly minted soldiers aboard the ship, he’d volunteered to fight in the Spanish-American War because he belonged to a generation bereft of its own. The Civil War had ended thirty-three years earlier, within the memory of grandfathers, fathers, uncles and neighbors. Their privations and sufferings had receded into legend but rather than teach their sons and grandsons that war is horror, they’d instilled the opposite sentiment. War makes men and Carl’s cohorts wanted to prove themselves on the battlefield.

The Rita was the first vessel captured in the conflict that had begun less than four months earlier. She’d been a lumber-hauling ship that creaked and rolled even through calm seas. Around Carl, men who two days earlier were full of bravado, willing to shoot and be shot at by the Spanish, now moaned and retched into buckets. Their groans, the odor of sweat, vomit, metal and gunpowder was far from what Carl had imagined when he signed up. How they could battle the enemy after such a night was beyond his grasp.

“Think we’ll see some action today?” another recruit asked when Carl joined those on deck. A haze eddied in melancholic streaks around the hunched figures.

“I don’t suppose they brought three thousand men on nine transports down here just for show,” he answered, his vowels flat and nasal.

Six days after they steamed from Charleston, Company C, Sixth Infantry Regiment of Illinois Volunteers had arrived in Havana, they learned Cuba’s eastern province had been taken but they were not to set foot on Cuban soil. Not only were their services unnecessary, the command ordered them to stay on board because an epidemic of yellow fever had already felled over four hundred troops. The Rita put out from Guantánamo Bay but the soldiers were unsure where they were going.

On July 25, they sighted a long beach, and beyond, gentle mountains bathed in fog.

“There’s Parta Rica,” someone called out.

A blast shook the transport, and some of the soldiers on deck panicked.

“It’s the Gloucester, pummeling the hell out of ‘em!” All eyes turned to the left, where a Navy gun boat was bombarding the shore. Revolver and rifle fire was returned, ineffectual against the big guns of the United States. To the right, landing boats floated toward the coast as the mist and smoke dissipated. A village faced the sea, behind it were tilled fields, barns and a chimney dominating the landscape. Carl recognized it as a sugar mill like the ones they’d passed in Cuba.

The infantrymen lined up. Carl adjusted his cartridge belt, secured his rifle, pushed his flat-brimmed hat low over his forehead, grabbed the rope ladder, and climbed down to the landing boat. The men around him, mostly as young and inexperienced, were grim as they were rowed ashore, their rifles ready, their eyes trained on the thick vegetation beyond the waterfront. He was afraid, but also exhilarated, as he imagined all men must be in the face of impending battle. Voices muttered about the size of the ships, the loud reports of the guns, the boats filled to capacity with Army men. They called to one another in muted tones, acknowledged each other with none of the bluster of the previous days.

They dropped into waist-deep water. Rifles aloft, they waded toward a beach shadowed by coconut trees. Carl had never seen palms up close and became aware this was his first step on foreign soil.

They’d landed in Guánica, a town whose single road was lined with dwellings whose roofs and walls were made from dry, long leaves and palm fronds. The place was deserted, but Carl had the eerie feeling he was being watched.

“Stop daydreaming and move,” the sergeant barked. They began their march, expecting to be shot at any minute. As the Regiment trudged further into the country, people emerged from behind shacks, mostly barefoot children and women. Some waved, others shouted “Puerto Rico americano.” Children ran alongside the troops, cheering and laughing, followed by their mothers yelling for them to come back.

The officers expected a cavalry attack and while no enemy had been seen, the soldiers were on edge. Nerves, the fatigue of the previous night, and the discomfort inherent in a march uphill under a burning sun added to their agitation. Like the others, Carl wore a pair of the same thick blue wool pants worn by the Army of the Potomac in 1865. His lower legs were covered from ankles to knees by stiff canvas leggings laced over boots. His long sleeve shirt was also wool, lighter than the pants, and buttoned to the collar. His felt brimmed hat was secured with a leather strap under the chin. He carried a cartridge belt, a rifle, a bayonet, a blanket roll, a canvas tent, and a backpack loaded with fifty pounds worth of canned rations and hardtack. Within minutes of the beginning of the march, he was drenched in sweat. The wool pants, wet with sea water, weighed him down and as they dried, became scratchy and infernally hot. A few soldiers fainted from sunstroke and had to be carried on stretchers, some raving, others limp as if dead. Some discarded supplies to lighten their loads, packed their uniforms and marched in underpants.

They tramped into a field as the sun reached its zenith, unloaded their knapsacks and tried to find shade among the trees where they ate cold canned beans and hardtack. The field echoed with the moaning and groaning of weary men, their colorful swears, the clatter of gear as it hit the ground. Below stretched a valley of incomparable beauty, plowed fields and jungle coexisting side by side, and in the distance, the turquoise, yes, truly turquoise-tinted Caribbean sea, placid and serene. Menacing the harbor were the nine transports and four gun ships of the US Army and Navy.

They marched until after it was too dark to see the road and waited, hunkered against the night, only slightly cooler than the day had been. If there was to be a battle, this would be the time. Insects swarmed, and the most consistent sound was hands slapping the back of necks followed by men cursing unpleasant encounters with nature. Sporadic gunfire echoed from a distance, but it died as suddenly as it started. Most of the soldiers dozed, but Carl was kept awake by the buzzing and stinging of mosquitoes. His fair skin was sunburned in every exposed part of his body and whatever had been covered was painfully alive with heat sores and rash. He had no one to blame but himself. He’d wanted to be a soldier, had wanted to experience war, had volunteered for the adventure. He was learning war wasn’t just about shooting people and being shot at. It was about the hardships of everyday life than about fighting the enemy–at least this war was.

On the third night of their march, rain fell over Puerto Rico. The dry, stacked palm fronds that served as walls and roofs on my grandparents bohío acquired a ripe smell. Water seeped through the gaps, soaked hammocks strung between rafters, clothes hanging from nails, the homemade tables and splintery shelves. Leaks sprang in unexpected places as José placed cans or gourds beneath them. Rain fell on Josefa, my great-grandmother running to the outdoor kitchen to struggle with the smoldering fire in the fogón where she boiled ñame and yautía Higinio, my future grandfather, had dug from the ground earlier that day. Rain fell on Company C, Sixth Infantry Regiment of Illinois Volunteers camped wet and miserable in the slopes, among them Carl Sandburg, now soaked to the bone, hunkered under a tattered pup tent, his left eye swollen, closed by mosquito bites. Rain usually fell in Puerto Rico in July and August harboring hurricane season. But given the circumstances, to some people at least, this rain, so insistent to get into every corner, protected or unprotected, seemed like a baptism or at least a cleansing in preparation for a new order.

On Thursday, July 28, 1898, three days after troops landed in Guánica, Major General Nelson A. Miles, commander of the invasion, issued a general proclamation in the only language he spoke to the people of Puerto Rico, who could not understand him even if they could hear him. It was the first public statement from his government on the island:

“In the prosecution of the war against the kingdom of Spain by the people of the United States, in the cause of liberty, justice and humanity, its military forces have come to occupy the island of Puerto Rico…They bring the fostering arm of a free people, whose greatest power is in its justice and humanity to all those living within its fold.”

On the same day of the speech, news reached Company C that a Protocol of Peace between the United States and Spain had been signed. They were ordered to Ponce from where they steamed back to the United States. Upon arrival in the Port of New York, the soldiers were hollow eyed, sunburnt, malarial, and fifteen to twenty pounds lighter.

On the island, military administrators set about creating the newly annexed United States territory into Puerto Rico Americano. They changed the spelling to Porto Rico to make it easier for English speakers to pronounce. They changed the official language from Spanish to English so the natives could learn and obey their commands, demands, laws and rules as if legislating the language also legislated their tongues. Violent opposition forced those two laws to be repealed. But without consultation from the native population, nineteen years later the United States government decreed American citizenship without voting representation in the US House of Representatives or Senate. Governance on the archipelago would be at the whim of the US President, who appointed military and business cronies as governors.

Decades after his return home, when Carl Sandburg was a famous poet and the celebrated biographer of Abraham Lincoln, he wrote about his role in the invasion of Puerto Rico. He was a reporter covering a speech by President Theodore Roosevelt, and perked up when he heard mention of the Spanish American War. The President grinned, his eyes twinkled. “It wasn’t much of a war,” he said, “but it was all the war there was.”

By then Sandburg understood that even though there was little fighting, he’d been part of a historical event.

“It was a small war,” he wrote in his autobiography, “edging toward immense consequences.”

Sandburg understood there would be repercussions, but when he went on his soldierly adventure, he didn’t foresee it would weigh and oppress generations of Puerto Ricans. We didn’t invite the United States to take over our nation, we didn’t ask to be citizens but we’ve carried the burden of decisions by men who didn’t know us, didn’t respect us, who supported local leaders who ultimately betrayed our dreams and struggles for independence.

Millions of us are now scattered around the world, forced from our homeland as our culture is plundered and our heritage devoured by business interests. Those Puerto Ricans who believed in the promises in local elections, and those who couldn’t or wouldn’t leave, were forgotten. Their jobs vanished when generous tax breaks for USAmerican businesses disappeared. Speculators extended credit to the struggling newly unemployed workers, obliging them to high interest commitments on loans without asking how an already strained economy could sustain the extortionate rates. The United States continues to impose excessive taxes on all goods brought into the archipelago and disallowing free trade. All imported goods must be delivered by USAmerican ships that charge the highest tariffs.

Puerto Ricans have sent tens of thousands of our sons and daughters into other United States sanctioned foreign wars to return home to brood, rage and suffer unhealed wounds on an archipelago devastated by neglect. No matter our sacrifices, we are viewed and treated as second class citizens in the United States. Our home islands, like the ship that carried Carl Sandburg and Company C, Sixth Infantry Regiment of Illinois Volunteers were war booty and like the Rita, Puerto Rico has been ravished, abandoned and forgotten to the tides of the United States’ hubris.

Esmeralda Santiago: Memoirist, essayist, novelist. Her most recent novel is LAS MADRES.

Editor’s Note: For more of Esmeralda Santiago’s writings, subscribe to her Substack.